ARTICLES

Over the course of my career, I've published a variety of articles. When I am asked for these articles, I find that they are difficult to find in their original published form.

As such, I'm providing reprints as a digital service which can be instantly purchased and delivered via PDF to your email! To order, just click on the picture or title of the corresponding article.

Military Articles

Maintaining the Santa Fe presidio horse herd, (real caballada) from the marauding Indians was a challenge for the eighteenth century New Mexico governors and military officers. Without horses, the presidio soldiers and the auxiliary Pueblo Indians were unable to defend themselves from or make counter-attacks upon the Apaches of various kinds, Utes, Navajos, and especially the Comanches.

After the Pueblo Revolt, these tribes had become expert horseman, raiding the Spanish and the settled Indians successfully. This eighteenth century document shows that the presidio officers, and governor, (Governor Olavíde de Micheleña), were very aware of the need for more and better maintained horses.

The Spanish Colonial baroque style of decoration found its way into the design of eighteenth century branding irons. A brand registration document of 1785 illustrates the brands and gives the names and comments about the registrants. The venta marks that canceled the original brand are also shown.

Three New Mexicans, Jacinto Sánchez de Iñigo, Ysidro Sánchez Bañales, and Francisco Xavier Fragoso were all eighteenth century travelers on the Camino Real, and they all left behind a story about the Camino. This was not intentional…they were all accused of a crime and brought before the alcalde and governor. In 1704 Jacinto Sánchez de Iñigo was brought before the Santa Fe magistrate accused of stealing buckskins when serving as a military escort to retiring governor Pedro Rodríguez Cubero; Governor Gervsio Curzat Góngora cashiered soldier Ysidro Sánchez Bañales from the Albuquerque squadron for insubordination in 1732; and in 1767 Xavier Fragoso defended himself before Governor Pedro Fermín de Mendiñueta for stealing a reliquary. Their recorded testimonies, along with those of their accusers and various witnesses, offer detailed if not always coherent accounts of their adventures and misadventures on the Camino Real. In all cases, we learn something about Spanish colonial justice, the behavior of presidio soldiers, and most importantly, the Camino Real.

In the early eighteenth century, it became apparent that the Santa Fe presidio, separated as it was from the southern line of presidios located south of the Rio Grande, stood along under the repeated attacks from the surrounding hostile Indian tribes. It also became apparent that the natural resources required to support the presidio and protect the colony, were limited.

In protecting the colony, a strong and well supplied presidio with an effective military strategy was essential. Governors used the strategies of gift giving and trade with the hostile tribes when possible, but more often they used the strategy of mounted armed troops. Using mounted troops rather than infantry was necessitated by the size of the colony, the long distance traveled in campaigns, and, more importantly, the increasingly effective use of cavalry by raiding tribes.

Though the Indians had possessed horses for some time, the number of horses was greatly increased by the Pueblo Revolt, with large of numbers of Spanish mares and stallions left behind when the colonists abandoned the area for El Paso. The warriors quickly adapted to the use of horses, with horse ownership becoming part of the culture and a sign of status. By the 1720s and throughout much of the eighteenth century, Santa Fe and New Mexico were considered to be under siege by the Apaches, Navajos, Utes, and the more recently arrived Comanches.

This article details the way the Spanish cavalry was organized and used. More specifically, the locations of the grazing pastures required for herds totaling as many as 2,000 horses, the competing interests of settlers for pasturage, and constant efforts to defend said herds from Indian raiders.

Santa Fe Neighborhoods

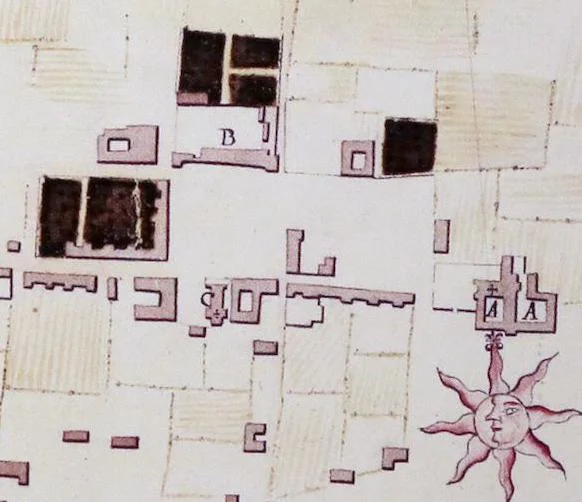

Generally speaking the structures in the Don Gaspar Architectural Historic District were developed between 1890 and 1930. The district does include portion of the Old Santa Fe Trail and Galisteo, (both historic routes to and from the city, and both are shown on the 1767 Urrutia Map). By 1912, much of the area was subdivided and developed, though remnants of the area still rural and the Old Santa Fe Trail was still dirt.

The district is located south of the State Capitol Building, and at the time of the 1983 survey consisted of 455 structures. It was predominately residential with a shopping center dating from the earlier part of the nineteenth century. The shopping center is located at the intersection of Paseo de Peralta and Old Santa Fe Trail. Also, some residences have been converted to office use along Paseo de Peralta following the construction of State office buildings in the 1950s.

Generally, the streets are in an irregular grid pattern, many of which are tree-lined. Most lots are fronted by walls and fences so that public rights-of-way are clearly defined. Stylistically the Spanish-Pueblo Revival style predominates, though many other styles are presented such as the Territorial Revival, Italianate, Prairie, and bungalow.

This study of the area was intended to gather information for a National Register nomination. Prepared by Ellen Threinen Ittelsen and Linda Tigges for the City of Santa Fe, the report includes historic photos and a list and map of structures recommended for significant and contributing status.

The Camino Del Monte Sol district, located on the east side of Santa Fe, is one of the older residential areas in the City, being occupied by the Spanish in the seventeenth century. The area includes remnants of several early acequias including the Acequia Madre. There are remains of the linear lot pattern with the long, narrow agricultural lots extending from the water sources, reflecting the Spanish colonial agricultural use of the land, though many of these lots have been divided leaving a final grained lot pattern. Structures in the district the district are generally variations on the Pueblo and Territorial Revival styles.

Today the area is may be best known for the structures and embellishment of the artists and writers who arrived in the 1920s. Visitors to the area may note the creatively carved doors and gates dating from that period.

In the summer of 1883, an architectural survey of the Camino de Monte Sol area was completed by Michael Belshaw for the City of Santa Fe for nomination of the area as a Historic District to the National Register. The survey report includes historic photos, a map of the area showing the proposed significant status of the structures, as well as a list of structures with addresses and names of the property owners in 1984.

While Santa Fe is known for its historic buildings, historic neighborhoods and streets were equally important in shaping its character. Santa Fe’s neighborhoods and streets are as much a reminder of its past as the plaqued historic structures. In 1988 in effort to better understand this significant part of Santa Fe’s urban history, a study was funded by the New Mexico State Historic Preservation Office and the City of Santa Fe of the thirteen neighborhood districts in the downtown and the surrounding area, many of which make up the City’s downtown zoning districts. The neighborhoods’ boundaries were chosen to include areas with a common history and pattern of development. This study includes a history of each neighborhood and describes the significant structures and streetscapes.

Staff for the project was Corinne Sze, Beverley Spears, Boyd Pratt and Linda Tigges who prepared the report using interviews with neighbors, newspaper articles, historic maps, County Commission and City Council minutes, and multitude of historic photos. The study also used subdivision plats from the nineteenth and early twentieth century, for example those of the Valuable Building Lots, the Staab Subdivision, Don Gaspar Square, the Duran Estate, and Fort Marcy Heights. Areas such as the Capitol and Cathedral complexes, and the downtown street realignment are provided with overlays showing original and subsequent development. The study also provides excerpts from the 1885-1886 Hartmann map, the Kings Maps, the 1924 City Official Map, and the map for the proposed location for the Mammoth Dam north on the north side of the City.

Most people, if asked, would most likely say that after the coming of the railroad to Santa Fe in the 1880s, the shift of land from Hispanic to American ownership was extensive if not complete. Indeed, anyone looking at the Santa Fe deed records for the period would be aware of the rapid turnover in property ownership, particularly in areas near the downtown and the railroad.

Things, however, are not always what they seem, and in fact, a close look at the 1880s land ownership data shows something different. Particularly challenged are old notions of the wholesale loss of urban land to non-Hispanics and the limited role of Hispanic women in inheritance and ownership of land. Also challenged is suggestion of the peripheral role of Hispanics in the 1880s in the buying and selling of land for investment purposes. Based on the data, though the newcomers had a clear and definite impact, for privately owned lots, Hispanic property owners were in the majority. In some categories, including downtown commercial lots, individual Hispanics constituted two-thirds of the property owners. In several cases, over a quarter of the Hispanic property owners were women. The data also shows that much of the land in Santa Fe’s downtown was owned by institutions, in particular, the Catholic church and the federal government.

In preparation for this article, data was derived from the 1885-86 Hartmann Map. The map showed lot lines, property ownership, structures, street names, some land uses, and arroyos and acequias. Measurement of the lots allowed calculation of the amount of land owner by individuals and government and religious institutions, and it allowed generation of numbers on ownership by ethnic group, gender and race.

The article includes the Hartmann Map and tables of the calculations.

In 1912 Santa Fe charmed visitors with its adobe structures, curving streets that followed the alignment of the acequias, and long and narrow lots that reflected the old agricultural pattern. It also had a water system that depended on individual wells, and a sanitary arrangement that used on-site disposal (out-houses), a combination that led to infectious diseases and epidemics.

The community leaders, concerned about the continuing prosperity of the town (the main line of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad went through Albuquerque, not Santa Fe) and the health of residents and visitors, and aided by the ever-energetic newcomer Harry H. Dorman, considered and eventually adopted a city plan that was intended to provide for improved health (a water and sewer system), efficient streets and city beautification. It was also tp encourage tourism and health seekers and thus give a boost to the faltering economy.

This article describes the planning process and its results, one of which was the unexpected consequence of the creation of the Santa Fe architectural style.

Santa Fe plaza

In 1990 a report, concurrent with an archaeological investigation of the Santa Fe Plaza, was prepared locating the Spanish Colonial cienega. The report used soils tests made for development in the area, the tests submitted to the City as part of the development review process. As part of the analyses, the tests identified the cienega soils as having a black, dense appearance, sometimes described as being like “black Louisiana gumbo.” The soils tests showed that the cienega extended to the south and east of the plaza, suggesting why occupation by the Spanish did not occur in that area. It also shows why the area was restricted to pasture for the presidio horse herds until the early 1800s, and why certain buildings in the downtown, even today, use sump pumps to remove water in their basements.

As part of the analyses, the tests identified the cienega soils as having a black, dense appearance, sometimes described as being like “black Louisiana gumbo.” The soils tests showed that the cienega extended to the south and east of the plaza, suggesting why occupation by the Spanish did not occur in that area. It also shows why the area was restricted to pasture for the presidio horse herds until the early 1800s, and why certain buildings in the downtown, even today, use sump pumps to remove water in their basements.

The plaza is the central feature of Santa Fe for tourists, dignitaries and locals. As a way of reminding all of us of the extraordinary history of the plaza, this study was prepared in 1990 to accompany an archaeological report on the plaza. The study was prepared by Stanley Hordes, Boyd Pratt, Cordelia Thomas Snow, David Snow and Linda Tigges.

Articles included are those on the plaza’s early history, its size and configuration as compared to that of other towns, and a review of seventeenth century Spanish land measurements. Other documents on Spanish Colonial armor, drought patterns in seventeenth century New Mexico, Spanish laws on urban theory and city planning, and a translation of the “Instructions to Peralta on Santa Fe by the Viceroy.”

In 1990-1992 when a team of archaeologists and local volunteers gathered together to dig test tranches on the Santa Fe Plaza, the expectations were high. Unfortunately, as the result of centuries of disturbance few architectural features were found. An Albuquerque Journal reporter smartly remarked that “When archaeologists dug up the Santa Fe Plaza to see what it had been in the 1600s, they discovered that it had been a plaza.” The artifacts were there, but they remained to be found by a later plaza excavation in 2016.

But all was not lost. A positive result of the study was the generation of reports and analyses done for the excavation. Some of this material is shown in the Santa Fe Plaza Study I available here. Study II include analyses of the faunal (animal bones) and wood remains that were found in the excavation. Also included are a short history of the Plaza, an environmental background of the plaza (floods, swamps, drought). In addition, this article includes a chronology of Plaza facts, and stories written by archaeologists, historians, and historic preservationists about events occurring on the Plaza as printed in the New Mexican. This article includes contributions from David Snow, Cordelia Snow, Stanley M. Hordes, David Grant Noble, Boyd Pratt, Linda Tigges, Corinne P. Sze, and Thomas E. Chavez.

José Román Ortega was a presido solider who left behind him a record of his life in the Spanish Archives of New Mexico, allowing us to see him as an individual. His great grandfather, Simón Ortega came with Vargas to New Mexico in 1692. He attempted to abandon the colony and was executed by Vargas, leaving his wife and son, Gerónimo Ortega (José's grandfather) left behind. José Román was a presidio soldier, a donor to the presidio fund for support of the American Revolution, and lived in a house on Palace Avenue. We know about him and his family because of presidio records and a lengthy probate case where the fifteen children from Gerónimo’s two marriages argued, called each other names, and generally disagreed over Geronimo’s meager estate.